Adam Nevill

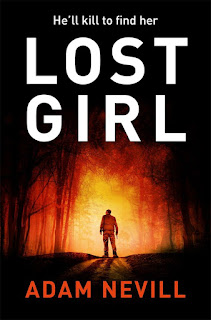

Adam NevillLost Girl

Pan, 22 October 2015

PB, 448pp

I'm grateful to the publisher for an e-copy of this book via NetGalley.

"Lost Girl" is the story of a missing child, and a father. As the world goes to hell, he focusses on his search for her. At any cost, whoever dies, whatever pain he has to suffer, he will find her.

Two years ago, Penny disappeared. She was playing in the garden by herself: her father, who should have been watching her, was upstairs, flirting by email. Is that why he is so driven to trace her, get her back? Is it guilt? Is it an attempt to atone, to flee from the empty life that's left after she was taken? Nevill doesn't quite tell us, preferring instead to communicate the simple fact of the father's drivenness, amplified by the fact that we never learn his name: throughout the book he remains, simply, the father.

This singleminded hunt is heightened because of the background to the novel. It is 2051, and runaway global warming has taken hold. The summers become hotter every year, crops are failing even in relatively buffered Britain, forest fires and droughts sweep the globe and India and Pakistan are on the verge of war over the declining rivers. A mass movement of refugees crosses Europe ("more and more coming in every day in great noisy leviathans of motion and colour and tired faces") and the population of the UK stands at 90 million (or 100, or 120... the Emergency Government isn't sure). Nationalists, jihadists and crime syndicates strut their stuff. Disease sweeps the globe (it's like the Four Horsemen have found a new partner,and enabler in climate change). Nobody has time or attention for one missing four year old. Except the father. Has he the right, we wonder, to pursue his own crusade like this? But if he doesn't who, who will?

It turns out that there are few like-minded souls who are happy to cooperate - or perhaps, one might think, use the father for their own ends, threatening sex offenders and imposing a kind of wild justice. It's a murky area and he'll take any help he can get - from the woman he only ever hears on the phone (except once...) and who he calls Scarlett Johansson, from the man who becomes Gene Hackman. They support the father, arm him and supply information - but can they really control what they've created?

Nevill's two most recent books, No One Gets Out Alive and House of Small Shadows have been unequivocal horror, albeit of a special kind: not so much spooks and spirits as the despair to be found in a dusty, abandoned country house or a rundown inner city terrace full of rustling plastic sheets and sticky, unwashed crockery. Here he maintains the emphasis on the seedy - as the world winds down, the father inhabits a string of decaying B&Bs, living off processed soya and Welsh rum. For normal people the world is going to rack and ruin. Only the super rich, or the criminal gangs, have any normality left. But the supernatural? The horror? Well, you'll have to decide, and you can call this a near future thriller or SF if you want, but for me, the horror (the horror!) is rather more stark because it is a credible portrait of what might actually happen, not a piece of fantasy. Perhaps we need more horror like this to shock us into action.

So while this book is not quite what I'd come to expect from Nevill, it is, I'd say, quite properly a horror story and the writing is superb (perhaps a little info-dumpy in places, maybe a few too many lists) but haunting, eloquent and deeply troubling: "...a never-ending carousel of flame, black smoke, glass-strewn streets, bodies under tarpaulins, riot shields glittering in sunlight, placards, aerial footage of felled buildings in other countries, churning brown water moving too fast through places where people had once lived, trees bent in half, tents and tents and tents stretching into forever..."

And that's before we even get to the nihilistic criminal cult of King Death, which is rooted in the decay of our civilization and seems to want nothing but darkness and chaos, but also to be a symbol of it. While the climate change is human caused, the book seems to say, it is still assailing our civilization from outside - and we can, with concerted effort, repel it, plan, allocate, rebuild, confront it. But the enemy we can't defeat, because it is internal, is the human will to death, the selfishness, stuff-you-I'm-alright which is at its purest form in the crime syndicates and the gated communities of the rich, hoarding, thieving, fencing out, killing - a microcosm of what went wrong to cause the disaster in the first place, carrying on as normal, learning nothing.

This is a chilling vision of the future. And normally one might gain some relief from a horror story when the book closes and the bad things end, on closing this, my thoughts were rather that they might only be starting.

No comments:

Post a Comment